W20 is an integration framework for the AngularJS-based Single Page Applications (SPA). It offers a modular programming model based on fragments and high-level services to accelerate your Web development.

Fragments and configuration

W20 and its applications are organized around the idea of fragments.

What is a fragment ?

A W20 application is made of several fragments that brings different concerns to the application. A fragment is a collection of web resources (JavaScript AMD modules, stylesheets, HTML templates…) that often but not necessarily depends on each other. The dependency between modules inside a fragment is orchestrated by the use of the RequireJS library.

Think of a fragment as a coherent set of resources linked together for the purpose of organization and reusability. By including and configuring a fragment you can bring the corresponding aspect and/or asset to your web application without having to worry about the intrinsic details of the fragment itself. Inside a fragment, the module dependency system guarantees that the dependencies of a module will be loaded before the module itself. This is especially important for large applications that often require an important number of JavaScript modules.

Fragments vs modules

When we talk about a module, we refer to a JavaScript AMD module, as used in the RequireJS library. That is, to say thing shortly, a .js file

whose content is wrapped in a define call (AMD modules are explained in greater detail further down). A fragment on the other hand is a collection of modules.

It is described by a manifest which exposes configuration properties. When you include and configure a fragment in your application you can generally choose

which modules to activate inside of it.

Fragment manifest

Each fragment contains a JSON manifest that serves as a descriptor for the fragment configuration possibilities. The fragment manifest has two main goals:

- To expose the available modules of the fragment and their available configuration options. It is important to understand that the fragment manifest does not configure the fragment. It exposes what configuration will be possible according to a configuration schema. In the next section we will see how to actually configure the fragment when you declare it inside your application manifest.

- To allow the declaration of additional RequireJS configuration. On application start, each RequireJS configuration of each fragments, if present, are merged together.

The properties of a fragment manifest are:

id: a mandatory string with no space which identifies the fragment. No fragment with the same id can be included at the same time in an application.name: an optional name for the fragment.description: an optional description of the fragment.requireConfig: an optional object with the properties of a RequireJS configuration object. In the example below we add a simple RequireJS configuration for module mapping (this allow to «map» a module to a name, which can be used for creating aliases or for module substitution). For an exhaustive list and description of the RequireJS configuration options, please have a look at its API. Remember that this configuration will be merged with all the other declared fragment configuration on application start.

{

"id": "demo-fragment",

"requireConfig": {

"map": {

"*": {

"mappedModule": "path/to/module/to/map"

}

}

}

modules: an optional object whose keys are the name of the exposed modules of the fragment. The value of those keys is an object with the module path and the configuration schema. The configuration schema contains the name of the configuration properties available for the module. In the example below we expose a module «demoModule» inside a fragment with id «demo-fragment» and a configuration property named «demoConfig» of type string for the module demoModule.

{

"id": "demo-fragment",

"modules": {

"demoModule": {

"path": "{demo-fragment}/modules/demoModule",

"autoload" : true,

"configSchema": {

"title": "Demo module configuration",

"type": "object",

"additionalProperties": false,

"properties": {

"demoConfig": {

"description": "A description of the demoConfig property",

"type": "string"

}

}

}

}

}

}

There is a few additional things to note in this last example:

- In the

pathproperty we used the fragment id enclosed in curly braces ({demo-fragment}). This alias is automatically registered based on the fragment id and points to the location of the fragment manifest (it is a RequireJS mapping). You can (and should for reusability consideration) use this alias in all other fragments and in the application to refer to the fragment location. - The

autoloadattribute specify if the module should be loaded automatically or only if required by another module. By «required by another module», we refer to the AMD definition and the dependency management between modules as used in RequireJS (through the use of adefineorrequirecall). If not specified, the module will not be autoloaded. - The

typeproperty of the «demoConfig» option has been specified as a string. This means that when the property will be given its value in the application manifest, passing a type other than a string will raise an error. The other type available are object, array, boolean and number. - The

additionalPropertiesproperty of the configuration schema specify if additional properties can be given when configuring this module in the application manifest. In this example, trying to configure any other property than a «demoConfig» one for this module in the application manifest will raise an error.

The configuration schema is optional. You can simply declare the module along with its path and eventually ask for it to be autoloaded (false if not specified). This is often the case when you simply want to include a module that has no particular configuration in your business fragment.

W20 is packaged and distributed as multiple fragments. Your application will then be composed of those fragments and your own business fragments. Now that we have a better understanding of the notion of fragment, we can proceed to the configuration step in which we actually include and configure those fragments in our application.

Configuration

Application configuration happens in an application manifest. This manifest must be named w20.app.json because, in the absence of a remote manifest, the framework will fall back to looking for a JSON file with this name at the application root.

The role of the application manifest is to reference fragments through their manifest URL and configure them specifically for the application.

Fragment declaration

To include a fragment in your application, specify the path of the fragment manifest as a key.

{

"bower_components/w20/w20-core.w20.json": {}

}

The w20-core fragment will be loaded with all its modules whose autoload property is set to true. An alias {w20-core} is now

pointing to bower_components/w20, the location of the fragment manifest.

bower_components is the default name of the folder in which Bower installs the web dependencies. Bower is one of the most popular

package manager for web application. It should be installed to ease application development and/or use the w20 application generator. W20 fragments are available

in the Bower registry and will be installed to the bower_components folder if you choose this way of installation.

Fragment configuration

Declaring a fragment like above can sometimes be enough. Autoloaded modules will be available and that may be sufficient.

However, most of the time, you will configure the fragment’s modules according to your need or because an explicit configuration value is required.

To configure the modules of the fragment add a modules section:

{

"bower_components/w20/w20-core.w20.json" : {

"modules": {

"application": {

"id": "my-app"

}

}

}

}

In the above configuration, the application module of w20-core will be configured with the corresponding object (defining

the unique identifier of the application in this case). This module is normally defined as automatically loaded so this

definition will only serve to configure it. To load a module that is not automatically loaded without configuration, just

specify it with an empty object:

{

"bower_components/w20/w20-core.w20.json": {

"modules": {

"application": {

"id": "my-app"

}

}

},

"bower_components/other-fragment/other-fragment.w20.json": {

"modules": {

"my-module": {}

}

}

}

In the example above «my-module» will be loaded without any configuration. If it was not declared and the module was not set to be autoloaded, «my-module» would not be loaded on application start even if it belongs to the «other-fragment» fragment.

If a configuration JSON schema is provided for a specific module in the fragment manifest, the configuration specified here will be validated against it. Also, if a default configuration is provided for a specific module in the fragment manifest, the configuration specified here will be merged with it, overriding it. If no default configuration is provided, the configuration is provided as-is to the module.

Summary

Masterpage

W20 uses AngularJS as a core framework for application development.

Thus, its applications are Single Page Application (SPA).

Only one HTML page is served with an outermost html doctype and a root tag <html></html>. This page is called the masterpage.

The masterpage serves two roles:

- Instruct the browser to load the RequireJS library with the w20 loader as the main module. The w20 loader is a module of the core fragment and

referenced in the

mainattribute of the script which loads RequireJS and who will take care of bootstrapping the application. Aw20-appattribute is mandatory on the root element of the masterpage. Application loading is explained in further details in the following section. - Declare the unique

ng-viewelement of the application which will include view templates. View change is handled through client-side routing which associates an URL to a template. This template is rendered in theng-viewtag.

<!doctype html>

<!-- Sample masterpage for a W20 app -->

<html data-w20-app>

<head>

<title>Application title</title>

<script type="text/javascript"

data-main="bower_components/w20/modules/w20"

src="bower_components/requirejs/require.js">

</script>

</head>

<body>

<div data-ng-view></div>

</body>

</html>

You can notice that HTML attributes that are not part of the HTML specification (such as w20-app or ng-view) are prefixed with

«data-». This allow to keep templates valid against HTML validator by defining those attributes as custom attributes.

Note that the w20 module is referenced without the .js extension. It is a common mistake to include the .js extension while referring to module but this is not accepted by RequireJS. The module file name is «w20.js» but it must be referenced by «w20» only.

Additional configuration can be provided:

The

w20-appattribute can be provided with the URL of the application manifest as the value:<html data-w20-app="/resources/configuration"> ... </html>In that case, a request is made for retrieving the remote configuration. Without any value provided, the w20 loader will look for a

w20.app.jsonat the same level as the masterpage.The

w20-app-versionattribute, when provided a value, will append this value as an extra query string to URLs of resources. This is useful for cache busting.<html data-w20-app data-w20-app-version="1.0.0"> ... </html>The

w20-timeoutattribute specify the number of seconds to wait before giving up on loading a script. Setting it to 0 disables the timeout. The default if not specified is 7 seconds.<html data-w20-app data-w20-timeout="3"> ... </html>The

w20-cors-with-credentialsattribute accept a boolean that specify if whether or not cross-site Access-Control requests should be made using credentials such as cookies or authorization headers. By default the value is false.<html data-w20-app data-w20-cors-with-credentials="true"> ... </html>

Core fragment

The core fragment of W20 is the most important fragment of the framework and the only one that is mandatory. It provides the fundamental aspect of the framework, mainly:

- An AMD infrastructure through RequireJS,

- An MVC runtime through AngularJS,

- Application loading and initialization through the

w20module referenced in the masterpage, - A permission model which enables to reflect backend security,

- Extensive culture support.

- Support for HATEOAS

No CSS framework is provided in the core fragment to let you free of this choice. However, you can simply add an appropriate fragment of W20 to bring frameworks such as Twitter Bootstrap (w20-bootstrap-3) or Angular Material (w20-material). For additional information, please consult the UI section.

The rest of this manual will focus mainly on the core fragment. Additional fragments documentation can be found in the corresponding section of the documentation.

The core fragment provides the w20 module which is responsible for application initialization. Let’s look at how a W20 application load

itself.

Application loading

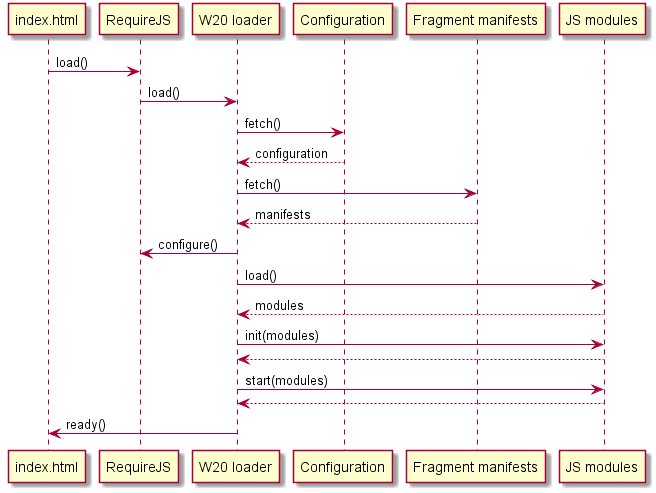

Once RequireJS is loaded, the w20 module becomes the entry point of a W20 application as the main module.

Think of it as a «fragment loader». Its initialization sequence is as follow:

- Loading and parsing of the application configuration (

w20.app.jsonor remote configuration). - Loading and parsing of all the declared fragment manifests.

- Computing of a global RequireJS configuration along with the list of all modules to load.

- Loading of all modules needed at startup time at once.

- Initialization of each loaded modules through their lifecycle callbacks (pre -> run -> post).

The last phase should be a little bit unclear at this point because we did not introduce modules lifecycle yet. We included it here to give you the full initialization sequence for future reference. Modules are documented in the next section.

Modules

AMD

JavaScript logic in W20 are defined in AMD modules. An AMD module is defined using the global function define exposed by RequireJS.

AMD module can be named but it is strongly recommended that you use anonymous AMD modules, each one living in its own JavaScript file.

They have the following form:

define([

// (1) list of the dependencies of this module

], function(/* (2) list of injected dependencies (in the same order as (1)) */) {

// (3) module factory function body (private scope of the module)

return {

// (4) public signature of the module that can be injected

// when requested as a dependency of another module

};

});

Let us expand a little bit on each part of this module definition:

- (1) The list of dependencies is composed of path to dependencies of this module, which are often themselves AMD modules. The path can be an absolute path or a map key if a RequireJS mapping has been defined. Remember that fragments manifest location are automatically aliased by their fragment id enclosed in curly braces. This means that you can reference a W20 fragment or your own one as a dependency like this:

define([

'{w20-core}/modules/application',

'{your-fragment}/modules/your-module'

], ... );

Please note that modules are referenced without their .js extension.

Third party libraries location are also aliased. For instance AngularJS distribution location is aliased by {angular}.

This means that you can reference a dependency to angular.js with {angular}/angular.

(2) The last parameter to the

definefunction is the factory function. Its parameters are the public value returned by the dependencies defined in (1) in the same order. That is, if we take the example above, the public value of the «application» module as first argument and the public value of «your-module» as second argument.(3) The body of the factory function constitute the private part of the module. This part is not available to other modules.

(4) The return value of a module is the public part it exposes to the world. The value of this return will be what will be injected in other modules factory function if that module is a dependency of them.

define([

'{w20-core}/modules/application',

'{yourFragment}/modules/yourModule'

], function (applicationPublic, yourModulePublic) {

var privateValue = 'I am a private string';

return {

publicValue: 'I am a public string'

}

});

Now, if we suppose the module above to be named «demo.js» inside a fragment with id «example», if this module is defined as a dependency of another, the last one can access the publicValue property of the object.

define([

'{example}/modules/demo',

], function (demo) {

console.info(demo.publicValue); // "I am a public string"

});

Module configuration

To access the configuration of a module it needs to depend on the module module. This special module is used to retrieve the module id, its location

and the value of its configuration options (those declared in the application manifest).

If we suppose a module «sample» with the following configuration:

"some-fragment/path/some-fragment.w20.json": {

"modules": {

"sample": {

"prop": "Value of property one"

}

}

}

The configuration is retrieved inside the «sample» module like this:

define([

'module',

], function (module) {

var config = module && module.config() || {};

console.log(config.prop); // "Value of property"

});

The statement module && module.config() || {} is the idiomatic way of safely retrieving the module configuration.

Lifecycle callbacks

In the «Application loading» section we have seen that the initialization sequence ended with each loaded modules going through their «lifecycle callbacks». Actually this is only the case for modules that declares lifecycle callbacks. If a module does not declare any lifecycle callback then it is simply loaded.

Lifecycle callbacks happens when all fragments have been collected and the RequireJS

configuration has been merged. There are 3 lifecycle callbacks which runs in the order: pre, run and post.

- All of them are optional.

- It is guaranteed that every modules will run their

precallback before any other modules run theirruncallback. - It is guaranteed that every modules will run their

runcallback before any other modules run theirpostcallback. - A module dependency will have its callback called before the module requiring it.

To integrate a module into the lifecycle management of the application, you must add the following code to the public signature of the module (i.e the return value of the factory function):

return {

...

lifecycle: {

pre: function (modules, fragments, callback) {},

run: function (modules, fragments, callback) {},

post: function (modules, fragments, callback) {}

}

...

};

You can omit the unsupported callbacks (for instance, just leaving the pre one). If the loader recognize one or more

lifecycle callbacks, they will be invoked during W20 initialization with the following arguments:

modulesis an array of all public modules definitions,fragmentsan array of all loaded fragment manifests,callbackis a function that MUST be called to notify the loader that any processing in this phase is done for this module (including asynchronous processing). If a module do not call its callback, the whole initialization process is blocked for a specified amount of time. After that, it is cancelled and a timeout error message is displayed.

Lifecycle callbacks are useful hooks for application initialization. The pre callback for instance will run before AngularJS

initialization, the subject of the next section.

AngularJS initialization

Before AngularJS initialization, it is guaranteed that:

- All AMD modules needed at startup are loaded,

- Their factory functions have been run in the correct order,

- Their

prelifecycle callbacks have been run and all modules have notified the loader that they have finished loading their asynchronous resources if any.

AngularJS initialization is done explicitly with the angular.bootstrap() function on the document element. It occurs

in the run lifecycle callback of the application module. From this moment AngularJS initialize normally; you can read more

about the initialization process here.

AngularJS modules

AMD vs AngularJS modules

AngularJS modules are not to be confused with AMD modules. We said at the begining of this guide that when we refer to a «module», it is an AMD module. We will continue to do so and use the term «AngularJS module» to refer to the notion of module in AngularJS.

From the AMD point of view, AngularJS modules have no meaning. However, AngularJS modules are fundamental for structuring an application correctly.

What is an AngularJS module ?

AngularJS modules allow to register services, factories, controllers, directives, providers and other concepts such as configuration or run block. AngularJS modules are also fundamental for unit testing. Each AngularJS module can only be loaded once per injector. Usually an AngularJS app has only one injector and AngularJS modules are only loaded once. Each test has its own injector and AngularJS modules are loaded multiple times.

AngularJS module dependencies

Wait a minute. Did we not already talk about dependencies between modules ? Yes, we did. We talked of dependencies between AMD modules. But AngularJs modules can also list other AngularJS modules as their dependencies. Depending on an AngularJS module implies that the required AngularJS module needs to be loaded before the requiring AngularJS module is loaded.

// firstModule.js

define(['{angular}/angular'], function (angular) {

var firstAngularModule = angular.module('first', []);

});

// secondModule.js

define(['{angular}/angular', 'firstModule'], function(angular) {

var secondAngularModule = angular.module('second', ['first']);

});

In the example above the dependency between AngularJS modules is declared as an array in the second argument to the angular.module function. AngularJS maintains an injector

with a list of names and corresponding objects. An entry is added to the injector when a component is created and the object is returned whenever it is referenced using the registered name.

How does that fit with the dependency system between AMD modules ? It is important to remember that the purpose of AMD modules and AngularJS modules is totally different.

The dependency injection system built into AngularJS deals with the objects needed in a component while dependency management in RequireJS deals with JavaScript files. In other word,

if an AngularJS modules depends on another AngularJS modules, this means that they must be loaded in the correct order. The secondModule depend on the firstModule to be loaded first.

AngularJS modules and W20

To correctly initialize AngularJS, the application module must know all the top-level declared

AngularJS modules. To expose them properly, you must add the following code to the public signature of modules that

declare AngularJS modules:

return {

...

angularModules: [ 'angularModule1', 'angularModule2', ... ]

...

};

All angularModules arrays of AMD public signature modules are concatenated and the resulting array is passed to

the angular.bootstrap() function.

Note that you don’t need to add the transitive AngularJS modules.